Any fossil fuel infrastructure built in the next five years will cause irreversible climate change, according to the IEA. Photograph: Rex Features

The world is likely to build so many fossil-fuelled power stations,

energy-guzzling factories and inefficient buildings in the next five years that it will become impossible to hold global warming to safe levels, and the last chance of combating dangerous

climate change will be "lost for ever", according to the most thorough

analysis yet of world energy infrastructure.

Anything built from now on that produces carbon will do so for decades, and this "lock-in" effect will be the single factor most likely to produce irreversible climate change, the world's foremost authority on energy economics has found. If this is not rapidly changed within the next five years, the results are likely to be disastrous.

"The door is closing," Fatih Birol, chief economist at the International Energy Agency, said. "I am very worried – if we don't change direction now on how we use energy, we will end up beyond what scientists tell us is the minimum [for safety]. The door will be closed forever."

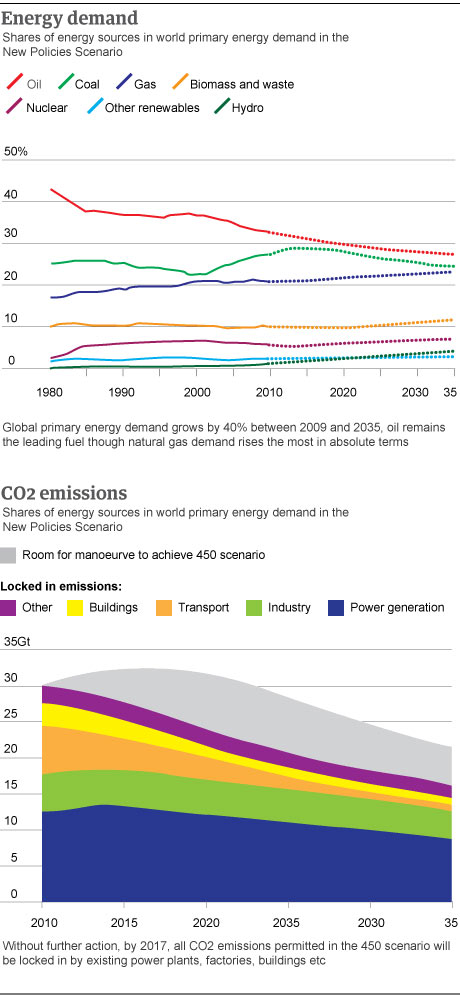

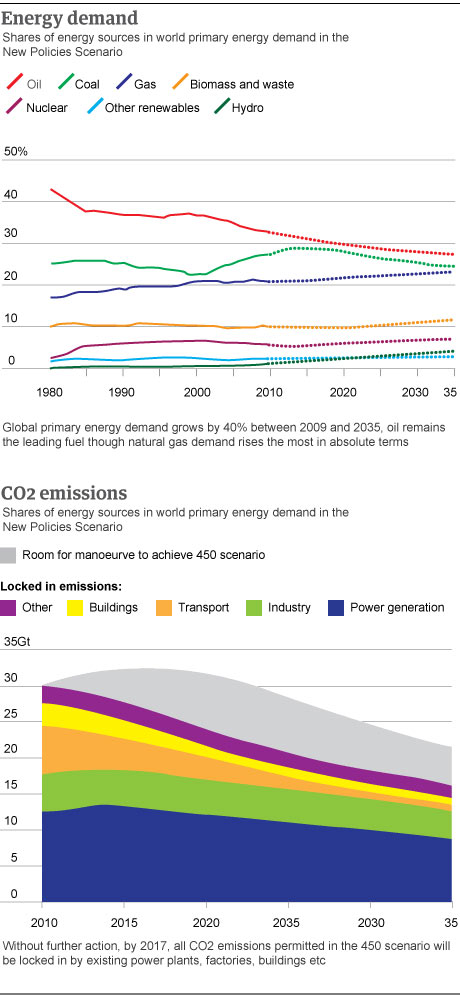

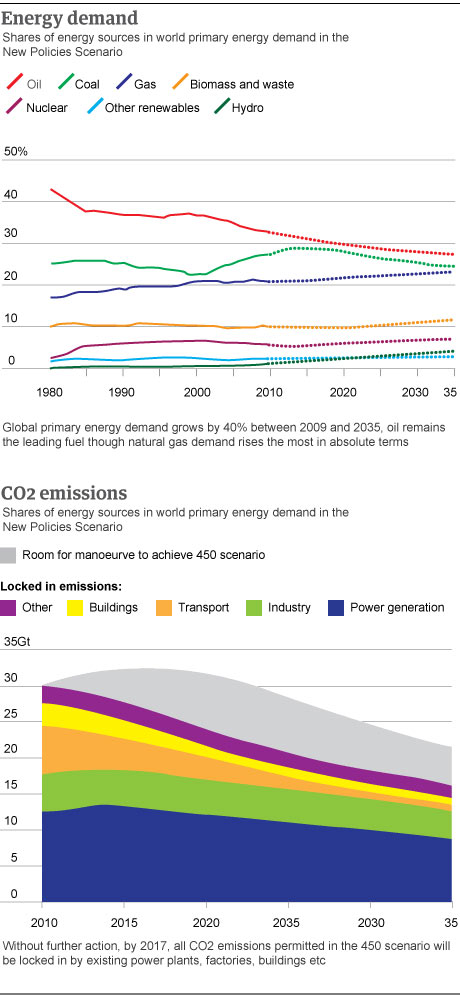

If the world is to stay below 2C of warming, which scientists regard as the limit of safety, then emissions must be held to no more than 450 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere;

the level is currently around 390ppm. But the world's existing infrastructure is already producing 80% of that "carbon budget", according to the IEA's analysis, published on Wednesday. This gives an ever-narrowing gap in which to reform the global economy on to a low-carbon footing.

If current trends continue, and we go on building high-carbon energy generation, then by 2015 at least 90% of the available "carbon budget" will be swallowed up by our energy and industrial infrastructure. By 2017, there will be no room for manoeuvre at all – the whole of the carbon budget will be spoken for, according to the IEA's calculations.

Birol's warning comes at a crucial moment in international negotiations on climate change, as governments gear up for the next fortnight of

talks in Durban, South Africa, from late November. "If we do not have an international agreement, whose effect is put in place by 2017, then the door to [holding temperatures to 2C of warming] will be closed forever," said Birol.

But world governments are preparing to postpone a speedy conclusion to the negotiations again. Originally, the aim was to agree a successor to the 1997 Kyoto protocol, the only binding international agreement on emissions, after its current provisions expire in 2012. But after years of setbacks, an increasing number of countries – including the UK, Japan and Russia – now favour postponing the talks for several years.

Both Russia and Japan have spoken in recent weeks of aiming for an agreement in 2018 or 2020, and the UK has supported this move. Greg Barker, the UK's climate change minister,

told a meeting: "We need China, the US especially, the rest of the Basic countries [Brazil, South Africa, India and China] to agree. If we can get this by 2015 we could have an agreement ready to click in by 2020." Birol said this would clearly be too late. "I think it's very important to have a sense of urgency – our analysis shows [what happens] if you do not change investment patterns, which can only happen as a result of an international agreement."

Nor is this a problem of the developing world, as some commentators have sought to frame it. In the UK, Europe and the US, there are multiple plans for new fossil-fuelled power stations that would contribute significantly to global emissions over the coming decades.

The Guardian

revealed in May an IEA analysis that found emissions had risen by a record amount in 2010, despite the worst recession for 80 years. Last year, a record 30.6 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon dioxide poured into the atmosphere from burning

fossil fuels, a rise of 1.6Gt on the previous year. At the time, Birol told the Guardian that constraining global warming to moderate levels would be "only a nice utopia" unless drastic action was taken.

The new research adds to that finding, by showing in detail how current choices on building new energy and industrial infrastructure are likely to commit the world to much higher emissions for the next few decades, blowing apart hopes of containing the problem to manageable levels. The IEA's data is regarded as the gold standard in emissions and energy, and is widely regarded as one of the most conservative in outlook – making the warning all the more stark. The central problem is that most industrial infrastructure currently in existence – the fossil-fuelled power stations, the emissions-spewing factories, the inefficient transport and buildings – is already contributing to the high level of emissions, and will do so for decades. Carbon dioxide, once released,

stays in the atmosphere and continues to have a warming effect for about a century, and industrial infrastructure is built to have a useful life of several decades.

Yet, despite intensifying warnings from scientists over the past two decades, the new infrastructure even now being built is constructed along the same lines as the old, which means that there is a "lock-in" effect – high-carbon infrastructure built today or in the next five years will contribute as much to the stock of emissions in the atmosphere as previous generations.

The "lock-in" effect is the single most important factor increasing the danger of runaway climate change, according to the IEA in its annual World Energy Outlook, published on Wednesday.

Climate scientists estimate that

global warming of 2C above pre-industrial levels marks the limit of safety, beyond which climate change becomes catastrophic and irreversible. Though such estimates are necessarily imprecise, warming of as little as 1.5C could cause dangerous rises in sea levels and a higher risk of extreme weather – the limit of 2C is now inscribed in international accords, including

the partial agreement signed at Copenhagen in 2009, by which the biggest developed and developing countries for the first time agreed to curb their greenhouse gas output.

Another factor likely to increase emissions is the decision by some governments to abandon nuclear energy, following the Fukushima disaster. "The shift away from nuclear worsens the situation," said Birol. If countries turn away from nuclear energy, the result could be an increase in emissions equivalent to the current emissions of Germany and France combined. Much more investment in renewable energy will be required to make up the gap, but how that would come about is unclear at present.

Birol also warned that China – the world's biggest emitter – would have to take on a much greater role in combating climate change. For years, Chinese officials have argued that the country's emissions per capita were much lower than those of developed countries, it was not required to take such stringent action on emissions. But the IEA's analysis found that within about four years, China's per capita emissions were likely to exceed those of the EU.

In addition, by 2035 at the latest, China's cumulative emissions since 1900 are likely to exceed those of the EU, which will further weaken Beijing's argument that developed countries should take on more of the burden of emissions reduction as they carry more of the responsibility for past emissions.

In

a recent interview with the Guardian recently, China's top climate change official, Xie Zhenhua, called on developing countries to take a greater part in the talks, while insisting that developed countries must sign up to a continuation of the Kyoto protocol – something only the European Union is willing to do. His words were greeted cautiously by other participants in the talks.

Continuing its gloomy outlook, the IEA report said: "There are few signs that the urgently needed change in direction in global energy trends is under way. Although the recovery in the world economy since 2009 has been uneven, and future economic prospects remain uncertain, global primary energy demand rebounded by a remarkable 5% in 2010, pushing CO2 emissions to a new high. Subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption of fossil fuels jumped to over $400bn (£250.7bn)."

Meanwhile, an "unacceptably high" number of people – about 1.3bn – still lack access to electricity. If people are to be lifted out of poverty, this must be solved – but providing people with renewable forms of energy generation is still expensive.

Charlie Kronick of Greenpeace said: "The decisions being made by politicians today risk passing a monumental carbon debt to the next generation, one for which they will pay a very heavy price. What's seriously lacking is a global plan and the political leverage to enact it. Governments have a chance to begin to turn this around when they meet in Durban later this month for the next round of global climate talks."

One close observer of the climate talks said the $400bn subsidies devoted to fossil fuels, uncovered by the IEA, were "staggering", and the way in which these subsidies distort the market presented a massive problem in encouraging the move to renewables. He added that Birol's comments, though urgent and timely, were unlikely to galvanise China and the US – the world's two biggest emittters – into action on the international stage.

"The US can't move (owing to Republican opposition) and there's no upside for China domestically in doing so. At least China is moving up the learning curve with its deployment of renewables, but it's doing so in parallel to the hugely damaging coal-fired assets that it is unlikely to ever want (to turn off in order to) to meet climate targets in years to come."

No comments:

Post a Comment